This article is part of my series that delve into how to optimize portfolio allocations. This series explains the mathematics and design principles behind my open source portfolio optimization library Quant_OptimalPortfolio. The first article here dealt with finding market invariants. Having done so, we must now estimate the distribution of the market invariants in order to extract useful information from them.

Estimating the statistical properties of data is a deeply researched field. The difficulty arises in a few ways:

- Choosing the distribution from which we are going to assume the data was generated from.

- Making the estimators robust so that they are not too sensitive to the changes in data.

- Fitting the data to the chosen distribution to obtain the best estimate effectively.

- Making sure the estimators generalize well to the population and not just the sample data.

Before we go any further, we need to formalize some of the terminologies here.

Estimator

Given a sample of data that is generated from some distribution with fixed parameters,

For simplicity, we assume the distribution can be fully characterized by the mean and variance (or standard deviation). Now, an estimator is essentially an estimate of the mean and variance of the distribution calculated using the sample data. As you can imagine, this problem is tightly connected with the structure of the data, the number of data points, how it is generated and if there are any missing values.

Given these issues, there are a number of methods of finding estimators from data. I split them up into three categories as follows:

- Nonparametric — this works well when there is a lot of data.

- Maximum Likelihood — this works better than nonparametric when dataset is smaller

- Shrinkage — this works best for either high dimensional or very small datasets

Since discussing all three methods in one article will make the article way too long, in this article, we explore the nonparametric estimators. In subsequent articles, I will discuss the other two methods of estimating fairly deeply.

Nonparametric

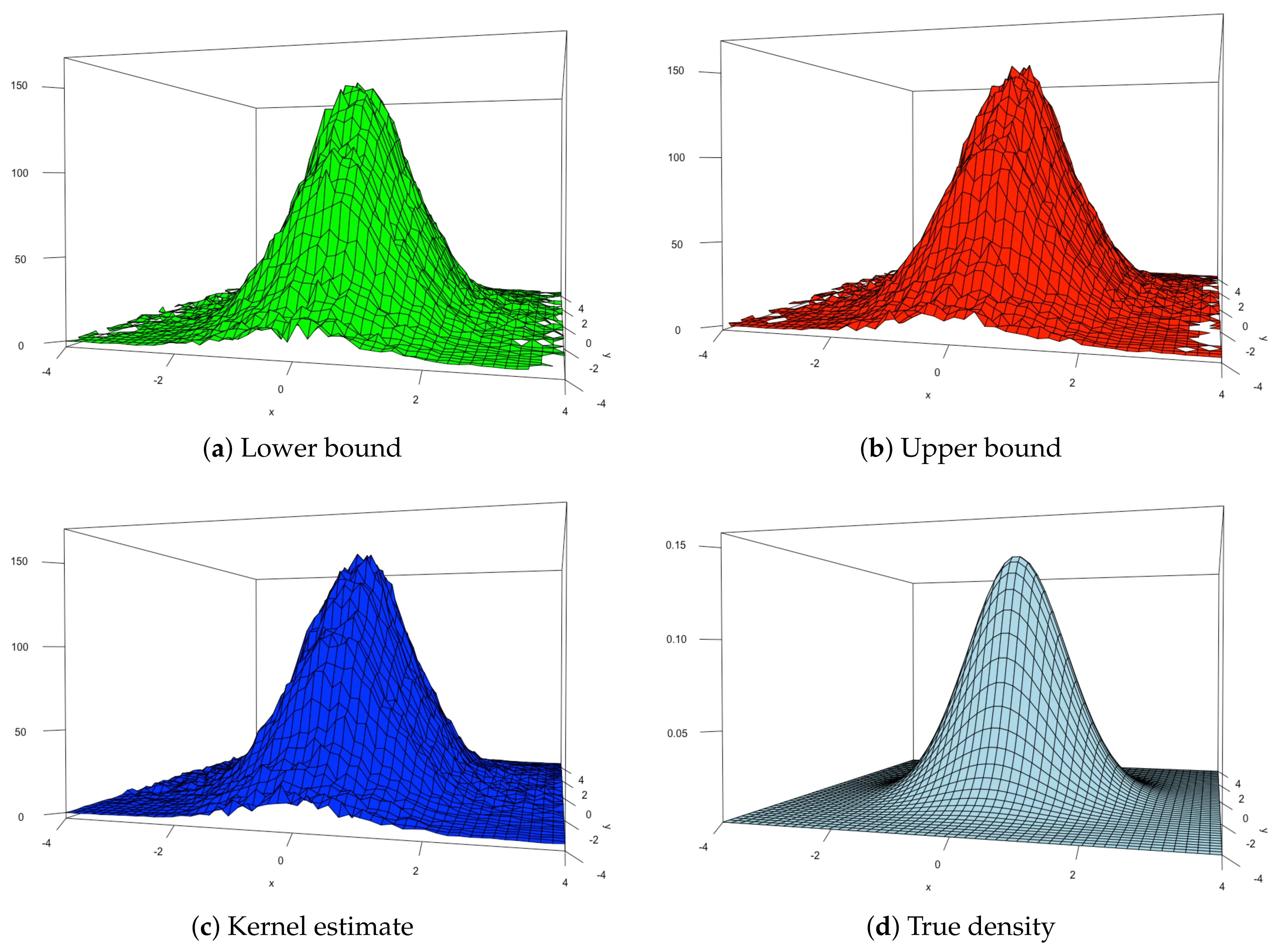

Nonparametric estimators are just as the name suggests. These estimators do not restrict themselves to any particular parameterized distribution. Instead, the data alone is considered and the distribution is modeled as an empirical distribution. An empirical distribution is essentially a distribution that has a kernel function at each data point. This kernel function is classical defined to be the Dirac delta function. However, due to the difficulty of doing calculus with Dirac delta functions, modern implementations consider the Gaussian kernel. In other words, the empirical distribution is a distribution that for every data point

In our case, we let the kernel function K be the Gaussian, so

Where the parameter gamma is considered to be the smoothing parameter, which can be thought of as the spread of the Gaussian at each data point. It is easily proven that this empirical distribution will yield a mean and variance equal to the sample mean and variance. Hence,

The empirical distribution seems simple enough to understand. This can be implemented as

def sample_mean(invariants, frequency=252):

"""

Calculates sample mean.

"""

daily_mean = invariants.mean()

return daily_mean*np.sqrt(frequency)

def sample_cov(invariants, frequency=252):

"""

Calculates sample covariance

"""

daily_cov = invariants.cov()

return daily_cov*frequency

The difficulty comes when we try to improve it to account for various errors. First, let us focus on the limitations of the empirical distribution.

Limitations

The nonparametric estimator suffers from a number of limitations. Firstly, in order to obtain a decent estimate of the true mean and variance, we need to have plenty of data. The large requirement of data is due to the Law of Large Numbers. The law states that as the number of data points tends to infinity, the sample mean and sample variance will tend to the population mean and population variance (with some conditions that out of the scope of this article). In other words, if we have an infinite dataset, then nonparametric estimators will be the best way to estimate the population statistics. However, in real life cases, data is not always enough (never infinity either). This causes the nonparametric estimators to loose accuracy and become a bad estimator.

Another limitation of nonparametric estimators is the sensitivity to data. Consider how adding or changing the individual data points affects the estimate of the mean and variance. Intuitively, the small change in one data point should not change the mean and variance of the population by a significant amount. However, this is not the case with nonparametric estimators. Since they are solely dependent on the data to derive the mean and variance, a small change in the data points results in a not so small change in the estimate. This can be formalized with the breakdown point of an estimator. The breakdown point of an estimator is defined as the minimum proportion of data points to be changed in order to change the value of the estimator. This in essence measures what we were discussing just now. The breakdown point of the nonparametric estimator is obviously 1/n. This is considered bad in the area of robust statistics.

Improving the Nonparametric

The benefit of using the nonparametric estimator is that there are no assumptions made about the nature of the underlying distribution. So, this would give us the most general result when finding estimators. Although it has limitations, we want to see if we can keep it for its general nature.

One possible extension if giving the data at different periods of time some notion of weight. In other words, we value the data from different points in time differently. An example of this is the exponentially weighted covariance estimator. I recently read about this in this article and it seems promising. The concept is similar to pandas.ewm where the each previous time step is given a smaller weight, usually to the power of some number less than one.

Which can be implemented as follows

def exp_cov(invariants, span=180, frequency=252):

"""

Calculates sample exponentially weighted covariance

"""

assets = invariants.columns

daily_cov = invariants.ewm(span=span).cov().iloc[-len(assets):, -len(assets):]

return pd.DataFrame(daily_cov*frequency)

Note that the weights need not always be exponential or in order. Consider the case where you might want to estimate the covariance matrix, but there is some volatility clustering within sections of the data. One approach might be to give more weight to the values within the cluster and less weight to values outside the cluster. The limitation of this approach is that it will need to be tailored to every dataset which might become computationally expensive when the dataset is very large.

Conclusion

To sum up, we find defined an estimator to be the ‘estimate’ of the parameters of the underlying distribution the data is being generated from. Then we discussed that there are three types of estimators: nonparametric, maximum likelihood and shrinkage estimators. We explored the nonparametric estimators and how to implement it in python. Considering some of its limitations, we proposed an extension of exponentially weighted covariance, inspired from an article and implemented it.

Going forward, we will be exploring maximum likelihood estimators and how they can be better than nonparametric estimators and under what situations should they be used.